Above: Peyote Meeting at Mirando City, Texas, from Reflections on the Peyote Road, by Jerry Patchen, ESPD50 (photo courtesy of Robert Black)

What is Peyote?

Peyote, scientifically known as Lophophora williamsii, is a small, spineless cactus native to North America, populating the vast desert thorn scrub that runs from the southwestern United States into north-central Mexico. It is commonly known for its psychoactive properties. Among its many alkaloids, peyote contains the naturally occurring chemical compound mescaline which has the ability to induce brilliantly colored geometrical visions. Classed as a controlled, Schedule I substance in the United States, Native Americans have had to fight hard for the sustained use of their sacred plant.

The sacramental use of peyote is the oldest known religious practice on the North American continent. By way of example, there are three archeological specimens of peyote that were discovered in the Shumla Cave in Pecos, Texas which have been radiocarbon dated between 3660 and 3780 BCE. Petroglyphs in the area adorned with peyote motifs have also been dated to the same period. Thus, the cactus has been used by indigenous groups in Northern Americas for millennia, being an integral part of the cosmology of Huichol peoples of Northern Mexico as well as the Native American Church.

Western Culture’s Misunderstanding of the Plant Medicine

Despite being given such reverence by indigenous peoples and the NAC, peyote has been extremely misunderstood by outsiders for centuries. Since their arrival in the New World in the early 1600s, Spanish colonists set about replacing native religions with Catholicism. Bernardino de Sahagún, a Franciscan friar, and missionary priest wrote about peyote:

“Those who eat or drink it see visions either frightful or laughable… it stimulates them and gives them sufficient spirit to fight and have neither fear, thirst, nor hunger… It causes those devouring it to foresee and predict; such, for instance, as whether the weather will continue; or to discern who has stolen from them…”

Upon coming into contact with peyote in Mexico, the Spanish colonialists considered it to be an anti-christian, “diabolical root” in direct opposition to the integrity of the Catholic faith. The Inquisitor General ordered Christianization at the point of the sword, and plants used in native rituals were condemned. In 1620, an official order was issued by the Inquisitors declaring that “no person of whatever rank of social condition can or may make use of the said herb, Peyote” as it was considered to be an “intervention of the Devil.”

Spanish Imperialists brought death and disease to Northern Mexico and with this its inhabitants fled, scattering south and west. One group, the Tarahumara Indians, made their home in the remote hills of the Sierra Madre Occidental. It is believed that their successors gave rise to the Huichol or Wixarika, who are the only remaining indigenous group in Mexico that continues to use peyote as a ritual sacrament.

The Native American Use of Peyote

‘Peyote Drummer’ Via Museum of Photographic Arts Collections

Meanwhile, north of the border the European colonization of America had begun. Over the span of a couple of centuries, the Native Americans saw their buffalo food supply deliberately wiped out, with each tribe experiencing its own genocide, land seizure, displacement, and removal to reservations.

Acclaimed ethnobotanist, Richard Evans Schultes, was among the first few Westerners to study peyote. In 1936, Schultes made his way to Oklahoma to study the ritual use of peyote among the Kiowa Indians.

It is thought that the Kiowa first came into contact with peyote in the mid-1800s through the Comanches. According to the seminal text Peyote Religion by Omer Stewart, the Carrizo Mexican Indians passed peyote use and rituals to the Lipan Apache, with the Apache going on to pass it to the Comanches, and finally it was passed from the Comanches to the Kiowa.

Anthropologist Wade Davis writes of the Native American’s connection to peyote in his book One River explaining that “peyote offered the Kiowa and the Comanche an astonishing affirmation of their fundamental religious ideas” in a time when their ways of life were disintegrating.

Legal Battles and the Native American Chruch

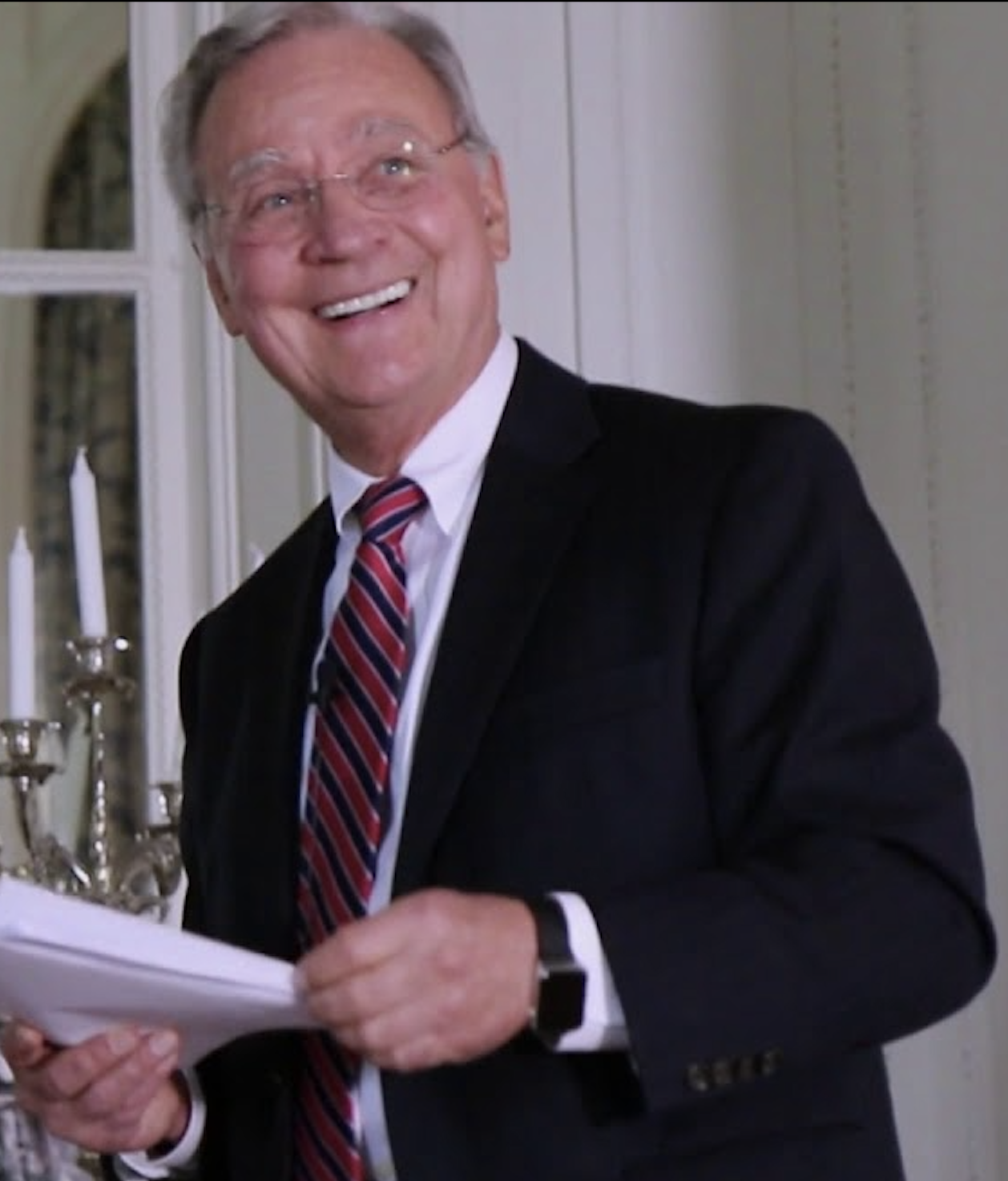

Jerry Patchen, a Texas attorney, and contributing author to our publication Ethnopharmacologic Search for Psychoactive Drugs has represented the Native American Church and US Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) licensed peyote dealers (peyoteros) harvesting and selling peyote to the NAC for over forty years.

During his career as a lawyer, he fought on the frontlines of the peyote wars, providing pro bono representation to Indians that were being charged with the serious offense of possessing a controlled substance. In his paper, “Reflections of the Peyote Road with the Native American Church – Visions & Cosmology” he expands upon his journey, helping to protect and secure the legal status of Peyote for use by Native Americans in NAC prayer services.

To learn more about the legal trials and tribulations faced by the Native American Church watch the video below, in which Jerry Patchen reflects on his career and shares his personal experiences.

In 1912, the Bureau of Indian Affairs tried to lobby for a federal law prohibiting peyote. This law was passed by the House of Representatives but rejected by the Senate. An Oklahoman senator was swayed by his Indian constituency, persuading his colleagues to vote against the bill. Following this, the Native American Church rallied the support of several anthropologists, ethnologists, and ethnobotanists in their fight to save their sacred medicine. Among them, Richard Evans Schultes had presented a vast bibliography as well as the insights from field research with the Kiowa. Finally, the U.S. Senate Committee accepted their conclusion that peyote was not a “habit-forming drug” and is used as a “religious sacrament”.

The efforts to prohibit the use of peyote ceased for three decades until the beginning of the 1960s countercultural movement in the 1960s where baby boomers discovered psychedelic substances and wanted to “turn on, tune in, drop out” en masse. Alarmed by the potential dangers of psychoactive substances, the U.S. government enacted The Controlled Substances Act of 1970, in which peyote was included in the drugs classified as Schedule I substances. Read more about psychedelics and the 1960s counterculture.

Patchen helped create and draft a plan of petitioning the U.S. Congress to pass the Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA) and to amend the American Indian Religious Freedom Act of 1978 (AIRFA) to expressly include peyote. This strategy was presented to Senator Daniel Inouye, Chairman of the Senate Committee of Indian Affairs at a public hearing in Oklahoma. The strategy succeeded with both Acts eventually being passed. Thus, the listing of peyote as a controlled substance does no longer applies to the sacramental use of peyote in bona fide religious ceremonies of the Native American Church. Later, this legislation played a key role in the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision to permit the religious use of ayahuasca. Patchen reflects that:

“Without the tenacious commitment of the NAC, there would be no legal use of Peyote or ayahuasca in the U.S. today”

What does the Future Hold for Peyote?

Lophophora williamsii by the botanical illustrator Donna Torres

In recent years, the greatest threat to peyote is its paucity and decreasing numbers. A convergence of factors such as illegal poaching, overharvesting, and conversion of its natural environment into agricultural land has led to a severe decrease in wild populations, making it a vulnerable species.

As early as 1995, American botanist Edward Anderson noted the change in peyote populations in his paper entitled “The “Peyote Gardens” of South Texas: a conservation crisis?”. Anderson theorized that the greatest threat to peyote was not the peyoteros who are registered with the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) and legally permitted to collect peyote to supply the Native American Church. In general, peyoteros are considered to be good conservationists, harvesting sustainably with the knowledge that their livelihood depends on stable populations of the plant.

Rather, Anderson identified the two most serious threats to peyote as “root-plowing [for agricultural purposes] and the locking up of ranches to the peyoteros” with most land being privately owned. Thus, a tension exists between land-owners and peyoteros who have to take out costly leases to harvest the peyote enclosed in private land. What’s more, is that it has become more and more difficult for distributors to gain the legal approval they need to collect peyote to sell to the Native American Church. A 2018 article by Daniel Oberhaus, stated that there are currently “only four peyoteros who are registered with the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) and legally able to collect peyote.”

Beyond this, the number of people consuming peyote globally exceeds the plants’ ability to regenerate. Since the 1960s, New Age psychedelic tourists have been drawn to the plains of Northern Mexico seeking visionary experience. This trend has also been amplified by the fanfare surrounding today’s psychedelic renaissance, with a renewed interest in the therapeutic potentials of visionary plants. This psychedelic tourism has inevitably has impacted the availability of peyote for the Huichol.

Peyote is a fragile species liable to become endangered. The plant itself is extremely slow-growing, taking many years to reach maturity, and people are harvesting it in a very negligent way. When harvesting is done sustainably, the top of the root hardens but the plant does not die and is able to produce more peyote in the future. If poor harvesting techniques are used, the entire plant dies.

To learn more about how to harvest peyote sustainably, check out this video uploaded by anthropologist, Bia Labate, interviewing Dr. Martin Terry from the Cactus Conservation Institute.

More about Jerry Patchen

Jerry D. Patchen, contributing author to Ethnopharmacologic Search for Psychoactive Drugs, is a Texas Attorney with four decades of experience litigating civil and criminal cases. Patchen’s work includes forty years of pro bono representation of the Native American Church (NAC) on behalf of American Indians to secure and protect their rights to religious freedom. Serving as an Officer in the NAC, he represented individuals charged in various states with possession of Peyote, winning every case. He also represented the Peyote dealers in Texas, who are licensed by the Texas DPS and DEA to dispense Peyote to Indians. Throughout his representation of the NAC Jerry, his wife, Linda, and their three children participated in Peyote meetings with Native American elders for decades.

Jerry D. Patchen, contributing author to Ethnopharmacologic Search for Psychoactive Drugs, is a Texas Attorney with four decades of experience litigating civil and criminal cases. Patchen’s work includes forty years of pro bono representation of the Native American Church (NAC) on behalf of American Indians to secure and protect their rights to religious freedom. Serving as an Officer in the NAC, he represented individuals charged in various states with possession of Peyote, winning every case. He also represented the Peyote dealers in Texas, who are licensed by the Texas DPS and DEA to dispense Peyote to Indians. Throughout his representation of the NAC Jerry, his wife, Linda, and their three children participated in Peyote meetings with Native American elders for decades.

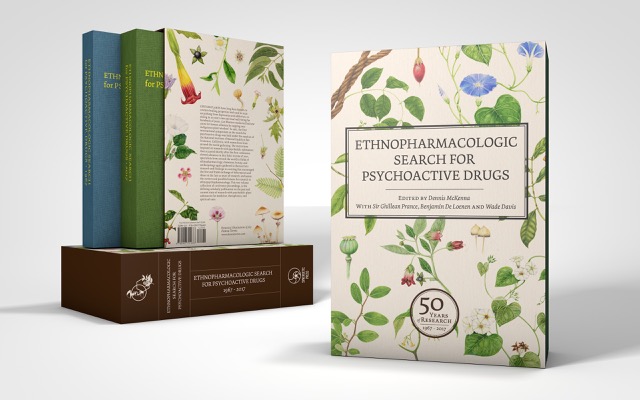

Ethnopharmacologic Search for Psychoactive Drugs: 50 Years of Research (1967-2017)

Certain plants have long been known to contain healing properties and used to treat everything from depression and addiction, to aiding in on one’s own spiritual well-being for hundreds of years. Can Western medicine find new cures for human ailments by tapping into indigenous plant wisdom? And why the particular interest in the plants with psychoactive properties? These two conference volume proceedings provide an abundance of answers.

Certain plants have long been known to contain healing properties and used to treat everything from depression and addiction, to aiding in on one’s own spiritual well-being for hundreds of years. Can Western medicine find new cures for human ailments by tapping into indigenous plant wisdom? And why the particular interest in the plants with psychoactive properties? These two conference volume proceedings provide an abundance of answers.

The milestone publication, Ethnopharmacologic Search for Psychoactive Drugs, emerged as the brainchild of Dennis McKenna. McKenna, having attained a copy of the original publication from the 1967 conference, found himself inspired to shape his career in light of the book, delving into a lifelong investigation of the pharmacology of traditional medicinal plants.