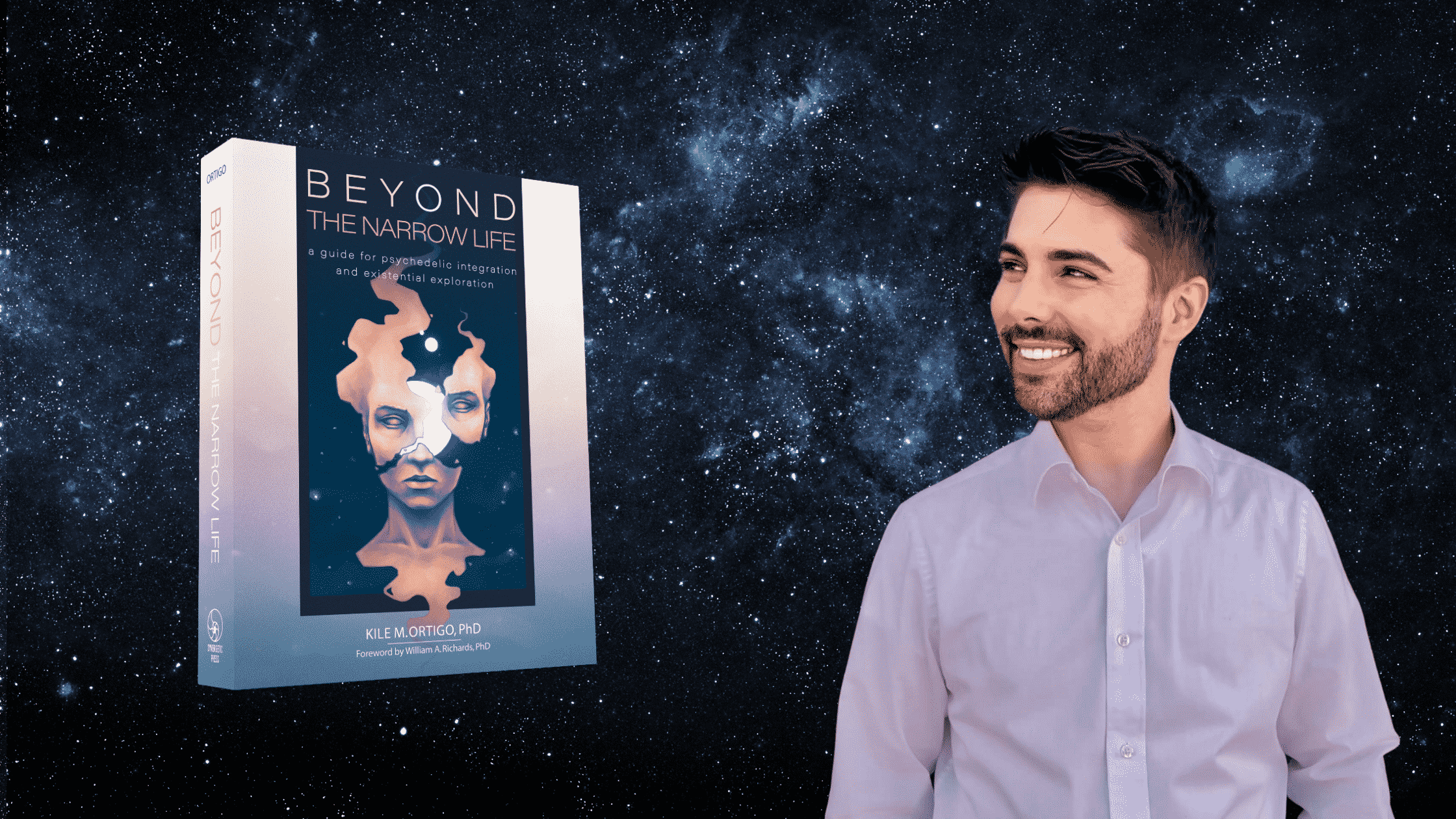

Author and award-winning clinical psychologist Dr. Kile Ortigo, speaks with Synergetic Press about his recently published book Beyond the Narrow Life: A Guide for Psychedelic Integration and Existential Exploration. Throughout the conversation, Ortigo reflects on what spurs our introspection, the benefits of becoming more comfortable with uncertainty, the role creativity plays in the process of individuation, and some of the pitfalls commonly encountered on the journey of integration and existential meaning-making.

Marco Orozco: The first question I have for you is broadly about your path towards arriving at the introspective journey. What is it about either introspection or psychedelics specifically, that ignited a spark in you to pursue writing Beyond the Narrow Life?

Kile Ortigo: So much of the book and of my work comes from within, it’s very much an authentic expression of my sense of curiosity and interest in so many different things about life. I knew I was going to do psychology in high school, but I didn’t know what I was going to do with it. And then when I got to college, there was just so much joy I had in learning not only about psychology, but a lot of the other things that are in this book, like film to mythology, Joseph Campbell, and Carl Jung.

Getting exposed to that at a young age very much inspired me. But I realized when I started to specialize in clinical psychology, a lot of these ideas and approaches, the depth-oriented transpersonal stuff, were kind of passé. And, really, if I didn’t go outside of the Department of Psychology, I probably would never have heard about Jung, certainly not about Campbell, despite enjoying Star Wars. This book was an opportunity to bring these big ideas back into the fold because there are such powerful, transformative, transcendent, mystical-like experiences that can happen during a psychedelic journey. It was an opportunity to bring back the depth of the psyche to modern psychology and to integrate the things that we’ve learned in the field for the past several decades.

Personally, it was a prime opportunity to synthesize many of my deeper interests, passions, and favorite fields of inquiry in a way that I hope is helpful for people and their own path of discovery and meaning-making in life. It was a creative project, first and foremost, but one that I believe can be useful in our individual journeys of what Jung called “individuation,” the lifelong process of personality growth and the striving for wholeness that we all can go into if we choose to say ‘yes’ to that journey.

MO: I ask because it seems like introspection and conscious meaning-making are not something that always come easily to everyone, not everyone is drawn to do this naturally. I’m curious if you see this book as being for people who have a kernel of introspection or self-reflection already planted within them? Or is it something that you’ve also written with people who haven’t had that experience in mind?

KO: I wanted to cast as big of a net as possible for the book while recognizing that if someone has zero interest or motivation to do deeper self-reflection, or to ask profound questions and tolerate ambiguity, this would be a hard book for them to read and work with. At the same time, people who by their own character proclivities don’t self-reflect a lot, often come to a point in life when they confront situations where it feels like the rug was pulled out from under them. It could be because of a tragic accident, a loss, or a major change in career. Or, even a very positive mystical experience can do this. Those people, when they hear what Campbell referred to as the ’Call to Adventure,’ a signal that there’s more out there than our everyday sense of mundane reality, which is not a reflection of reality itself, but our relationship to it, that those people when they hear that call, they can say ‘yes’ or ‘no.’ But however they respond, it’s an opportunity to go deeper, a realization that there’s more beyond one’s typical everyday ego awareness.

In approaching Beyond the Narrow Life, readers who are deeply self-reflective can do the activities independently on their own. But if someone needs additional support, I wrote it in a way that two or more friends can do it together. That helps with motivation, or it could help if you have a coach, and of course, if you have a therapist. This book is an opportunity to deepen relationships, which are often simultaneously important to people and challenging. There are all these different pathways, one can walk with or without the book when developing a relationship to its contents and using its exercises. That sense of connection to the inner mystery, of the psyche, and the mystery of our relationships and our shared reality, I think, is an exciting prospect for people who have never opened up to question some of these things.

MO: My next question is about ‘meaning making’ and finding meaning, and specifically, how the psychedelic experience and these potential medicines bring us closer to a more meaningful way of making choices and utilizing our consciousness and our freedom to make choices. What is it about the psychedelic experience that can bring us closer to a sense of ownership over our choices?

KO: It depends on the person and where they’re at in their life. The majority of people who are going to be reading this know about set and setting, the medicine, the dose, intentions, the importance of all those things. But part of that ‘set’ is just one’s internal psychological makeup, and life experiences. And for someone who is feeling a lack of meaning, or blandness about life, psychedelics can open the mind to color, possibilities, and depth which can be very meaningful.

“Wherever meaning is found in our personal values, in our worldview, relationships, community, etc., there’s always responsibility that’s tied to it. Psychedelics invite us to wake up to what intuitively feels meaningful and important to us, and then it’s up to us to try to apply that sense of meaning to our life, knowing that it’s never going to be perfect. Meaningful living is not a destination, rather it’s a process that unfolds.”

That meaning could be very individual, but often it involves a sense of interconnectedness, not just with other people, but with nature and even the cosmos. Sometimes psychedelics serve to shake up our sense of meaning, especially if it was rigidly defined, revealing that it may not be a core source of meaning. Psychedelics can create challenges around meaning or lack of it, as well as within the theme of responsibility, which is very important in existential psychotherapy. Wherever meaning is found in our personal values, in our worldview, relationships, community, etc., there’s always responsibility that’s tied to it. Psychedelics invite us to wake up to what intuitively feels meaningful and important to us, and then it’s up to us to try to apply that sense of meaning to our life, knowing that it’s never going to be perfect. Meaningful living is not a destination, rather it’s a process that unfolds.

MO: This ties into something I wanted to ask, which is that it feels like in our world and media, a lot of people are seeking to arrive at answers definitively. In your experience, how does psychedelic journeying help us become more comfortable with uncertainty and doubt? More comfortable with the accepting of our experiences as a process rather than a means to some end?

KO: For most of us, confronting uncertainty and ambivalence breeds anxiety, and that anxiety may be conscious or unconscious. When it’s unconscious, it gets transformed into something else. Sometimes it’s the opposite, an overconfidence in our worldview and sense of self. And psychedelics can certainly challenge us. What would be helpful in preparing for a journey, and in life more generally, is to increase our tolerance for ‘not knowing,’ and recognize that we cannot know everything.

“Even with the tools of history, scholarship, and science, there are always going to be mysteries and unknowns. And that certainly applies to our individual lives as we think about the future, which can breed anxiety for many people. It’s important to be able to think about the future, while also being able to stay grounded in the present.”

Even with the tools of history, scholarship, and science, there are always going to be mysteries and unknowns. And that certainly applies to our individual lives as we think about the future, which can breed anxiety for many people. It’s important to be able to think about the future, while also being able to stay grounded in the present. There’s a similar argument to reflecting on the past; everything has to be in balance and finding that balance is an individual journey. But by just avoiding these topics, we’re not actually doing ourselves any benefit, because it’s a temporary pushing away of the anxiety. This avoidance of decisions, while we’re still making them day to day, may mean staying in a job that’s unfulfilling or that has a negative impact on the environment, as an example.

These questions are hard to ask and reflect on but to gain insight and make meaningful changes, we need to do that. If we can tolerate and recognize anxiety, fear, and frustration as temporary, emotional experiences, they don’t have to control our behavior or decisions. If we can tolerate them, they usually dissipate and don’t become as strong. There’s a litany against fear in Frank Herbert’s Dune that I think is a great mantra. It communicates how our grounded awareness can help us move beyond automatic, primordial fear.

“I must not fear. Fear is the mind killer. Fear is the little death that brings total obliteration, I will face my fear, I will permit it to pass over me and through me. And when it has gone past, I will turn the inner eye to see its path. Where the fear has gone. There will be nothing, only I will remain.”

I found this after I wrote the book, but it’s an example too of the importance of stories and mythologies in helping us relate to the human experience, both its promises and perils.

MO: Jung suggests to certain patients to go into art-making, speaking about how that can transform us, or how it has the possibility of helping discover unconscious content. Part of that brings me to this question of what Stanislav Grof speaks of when he talks about the role of facilitators in journeying or healing. That is, activating what he calls the ‘self-healing intelligence’ within each of us. I relate that to something that comes through me when I’m making music or art in some way. I was wondering if you have any thoughts on this self-healing intelligence that takes place within us, and how that is manifested or expressed through psychedelic journeying.

KO: Jung talked about it as the capital S, “Self.” It’s an archetype of the psyche’s wholeness, often experienced in its broadest form as an inner godlike image. But the idea is that the Self is the totality of our unconscious and conscious parts. Parts include our conscious identity and ego all the way to what Jung described as complexes, our individual manifestations of archetypal patterns and relationships. Art is helpful in exploring unconscious content because words can create their own prison of abstract, intellectualized meaning-relations. It’s important in exploring our human experience of the psyche to look beyond words, and look at other types of symbolic relationships. Art is a great way to do that.

You mentioned being a musician, and music is something that’s great for our accessing of emotions and expressions of self, for listeners and musicians. Of course, we know music tends to be a very important factor in psychedelic journeys and holotropic breathwork sessions, etc.

The creation of art is a process of trying to bring to fruition some inner vision or drive for creativity that can come from the Self or other parts of our psyche. It’s a translation from the image or symbol in our mind to outward expression. But it can involve some pain and risk because the final product doesn’t always match our inner vision.

Even so, there’s a way to do creative work while acknowledging any perfectionism that can emerge when we’re at the edge of our skill. Certainly, my book felt impossible at different times as I was writing it. But for anything to be created, we must recognize such barriers and fears while remaining committed to the creative process. Joseph Campbell wrote in The Hero With a Thousand Faces that after going through the initiation and receiving their boon, the hero works to create an ‘elixir of life,’ some symbol that is healing for not only themselves but also for their community. Art is an elixir of life. It is uplifting to us, not that it needs to make us feel great all the time. Healing by engaging with art, whether by creating it ourselves or by deeply appreciating the art of others, is a worthwhile endeavor.

MO: What would you describe as some of the pitfalls of psychedelic use? The recreational use of psychedelics can awaken something deeper in people. Do you have any advice for people who utilize psychedelics outside of therapeutic settings, and are searching to make their journey more profound?

KO: I think it important to emphasize that psychedelics are, as Stan Grof said, nonspecific amplifiers of the psyche, or unconscious content. There are sometimes parts of ourselves that are out of balance, or that we are simply not prepared to confront.

That’s why in psychedelic-assisted therapy and in Indigenous and spiritual communities that use psychedelics, there are protocols or rituals in place to create a safe container for the journey. For example, it is important to have someone who is sober, trained, experienced, not new to this work and is very familiar with all the depths of the psyche, from the rosy to the complex, shadow side of things. Some people are using these substances because they read Michael Pollan’s book, or they hear about it from the New York Times without access to trained professionals from whatever tradition to support them in that work.

“The healing and transformative aspects of these experiences are often relational and involve a realization of interconnectedness. There are certainly lots of people that can have deeply meaningful experiences outside of clinical and spiritual contexts, but that’s not everyone.”

The healing and transformative aspects of these experiences are often relational and involve a realization of interconnectedness. There are certainly lots of people that can have deeply meaningful experiences outside of clinical and spiritual contexts, but that’s not everyone. There are risks that are involved, and without getting into specifics, things can go wrong. Many things went ‘wrong’ in the 60s in the West and in America, for example. I don’t, however, want to emphasize the negative. At the end of the day, people ought to respect the power of these substances and experiences, and by putting in the work to set up safe protocols, many of the risks can be mitigated.

This is part of what we call psychedelic harm or risk reduction. We need to educate our communities and make sure that we go about all of our life experiences as mindfully and respectfully as possible. In the book, I use the term ‘ego whiplash’. Namely, ego whiplash is when one delves into the depths of the mind and then goes back to everyday life immediately after as if nothing had happened. Sometimes after chasing ego death, people can have this ironic ego inflation that results. In our exploration of the Self, it’s easy for an inflated ego, inflated sense of self-importance to get brought into being. This is where we see self-proclaimed ‘shamans,’ and people who – I think often with good intentions – don’t realize the depth of complexity and breadth of experiences that people can have. Even Terence McKenna, the prototypical psychonaut, was seemingly fearless, but he had a journey that really shook him to his core and he couldn’t bring himself to talk about with others.

MO: This book is clearly a workbook with so many exercises and journeys within it. I’m curious as to what the process of creating it was like. I imagine that it required an enormous amount of introspection for you. And I’m also curious about how the process of writing changed you?

KO: The initial idea for the book was like a lightning bolt of insight and positive creative energy. Following that, I had to engage in the hard work of actually writing, refining, and going into the depths. The process involved a lot of ups and downs, especially because I started writing this book two and a half years ago. I did the bulk of the in-depth work last year (in 2020) when I began writing about death, loss, impermanence, loneliness, interconnectedness during the pandemic.

Besides giving me more time to focus and dedicate to the project, the pandemic gave me a sense of this parallel process of doing the work while I was writing it and creating a guide for other people. It’s part of my own ethics and sense of authenticity, to not ask or suggest to others something that I wouldn’t be willing to do or haven’t done myself. That was very much a part of these exercises and activities. This was from my own deeper reflections, explorations, and meaning-making process. But it has been a joy to pour so much life force into this book, and to see the energy coming out the other side when starting to hear the impact it’s having on people’s lives. That’s deeply meaningful to me and absolutely why I felt like I needed to do it. In many ways, really, the book was written through me, not simply by me. And now it’ll have a life of its own.