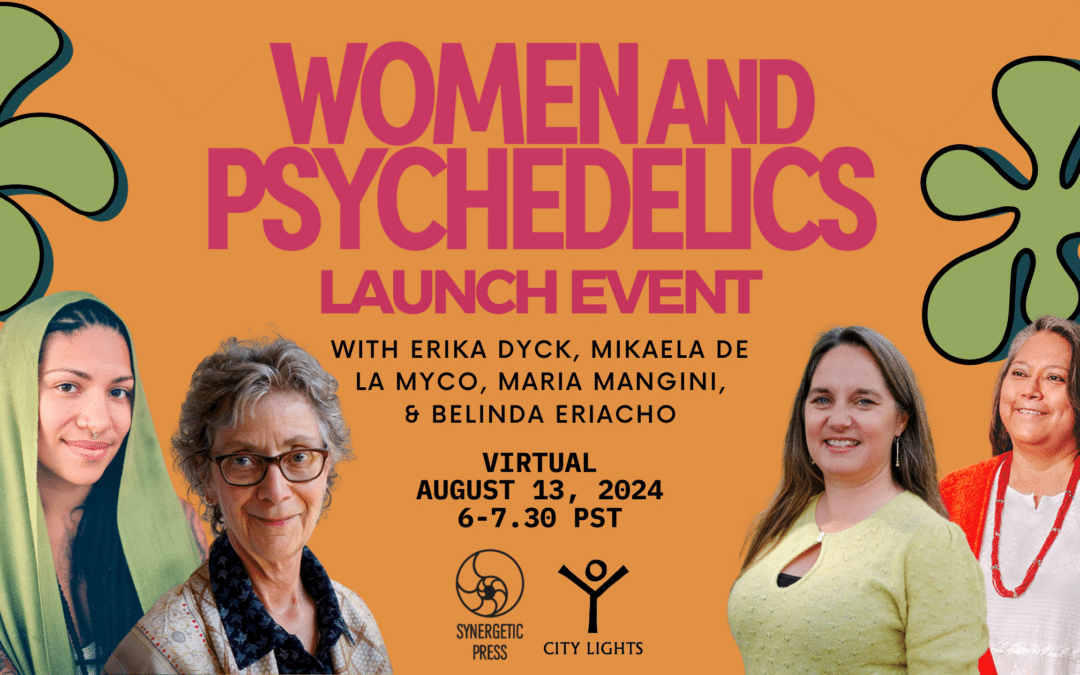

Women and Psychedelics Virtual Launch Event

TUESDAY, AUGUST 13, 2024, 6:00-7:30 PM PDT

Women and Psychedelics Virtual Launch Event

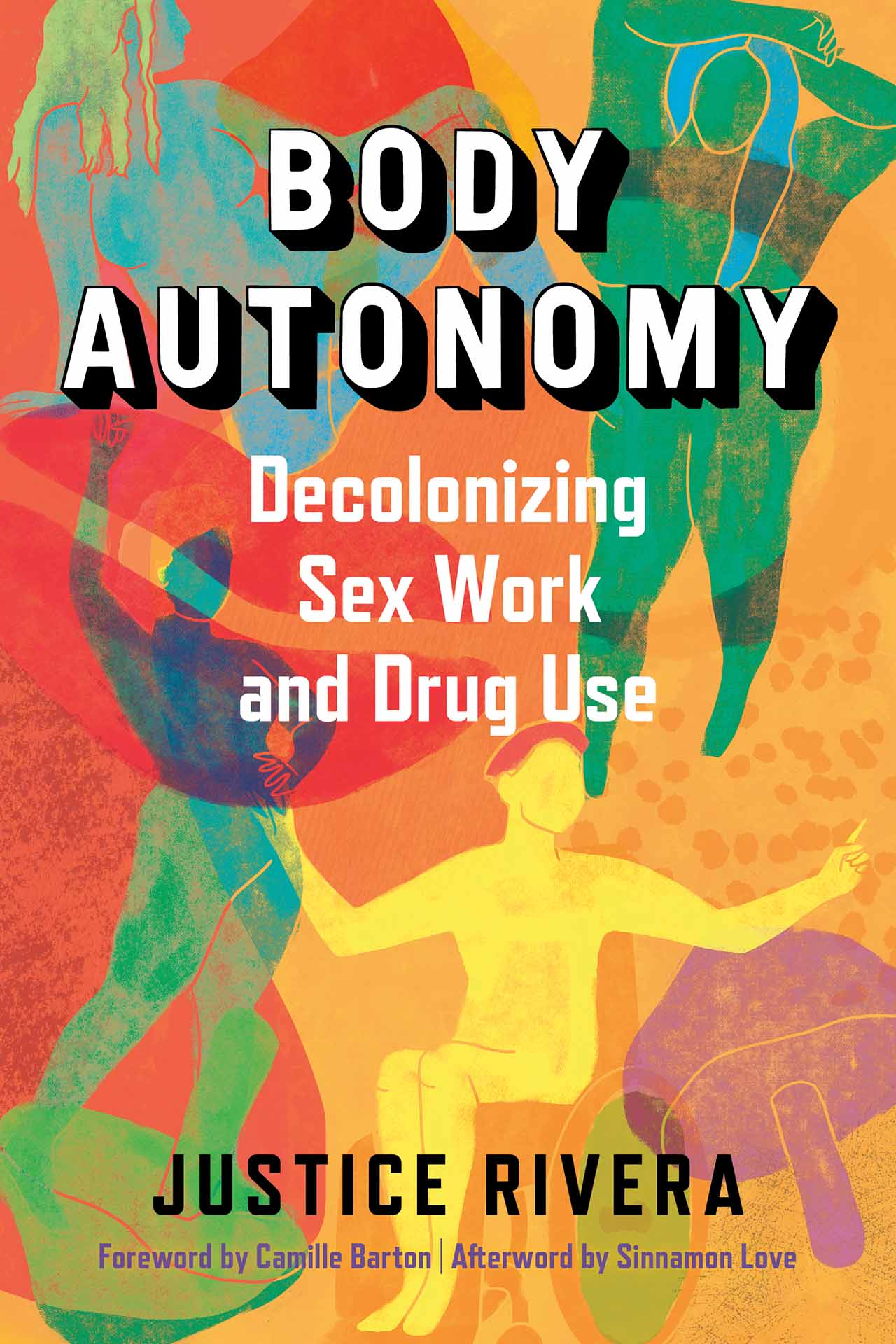

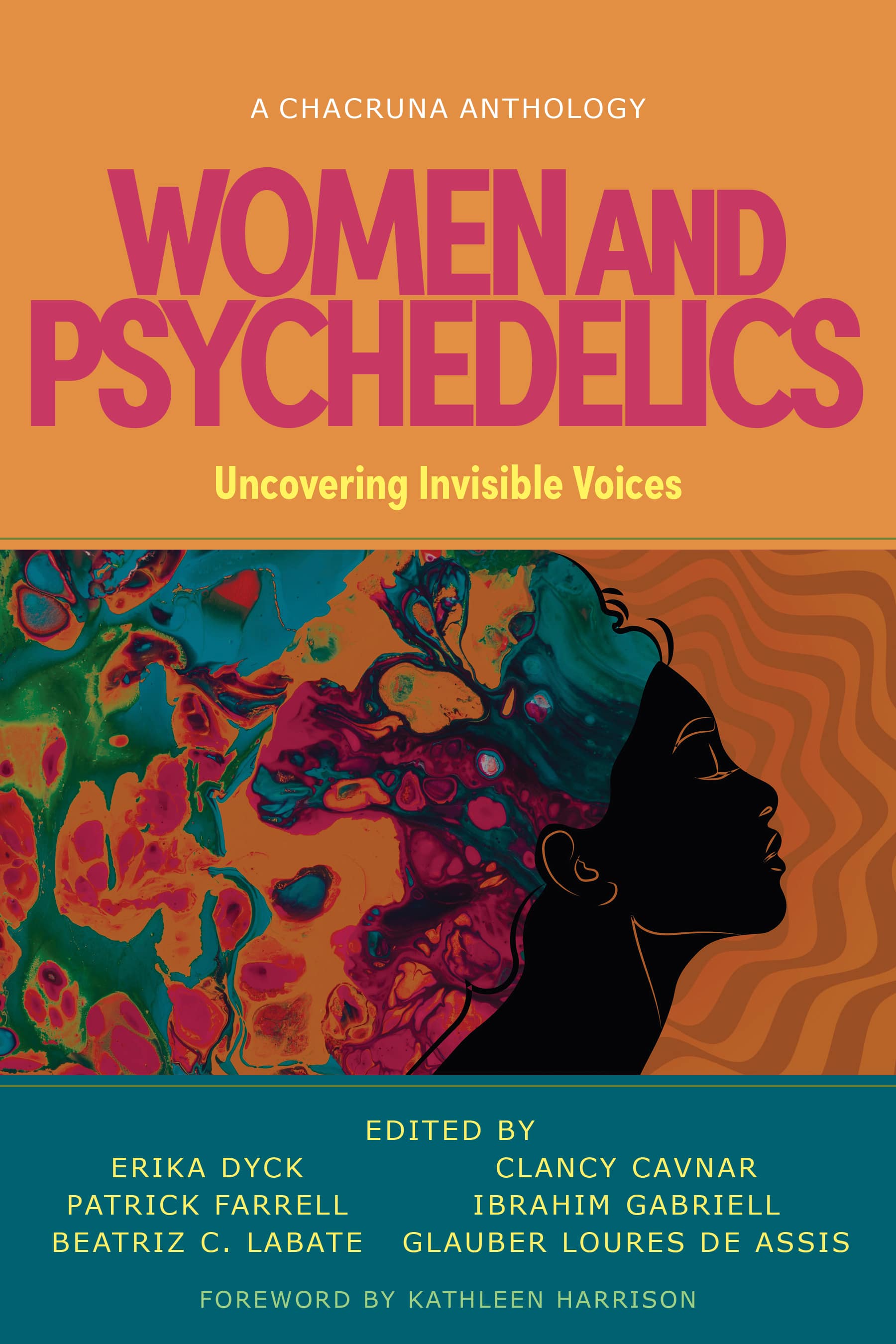

In the ever-expanding conversations around psychedelic medicines and their multitudinous histories, women’s voices and stories have been excluded and even suppressed. What profound contributions are living outside of this patriarchal lens? How do we understand the role of women in psychedelic history and the emergent present?

Join historian and co-editor of Women and Psychedelics: Uncovering Invisible Voices, Erika Dyck in conversation with Belinda Eriacho, Mikaela de la Myco, and Maria Mangini in highlighting some of the seminal women who have shaped, and continue to shape, the psychedelic landscape. This intimate, intergenerational conversation will explore the roles women have played in care work, from ritual rites of passage in the transpersonal domains of birth and death to the vital role that elders play in the psychedelic community. We will also examine how traditional gender norms have shaped the way psychedelics are perceived and utilized, using intersectional frameworks to explore how we can collectively create a more inclusive and equitable space for all.

This is a virtual event that will be hosted by City Lights on the Zoom platform.

Attend at this link: https://us02web.zoom.us/j/82420182310

You will need a device that is capable of accessing the internet.

About the speakers

Erika Dyck is a Professor and Canada Research Chair in the History of Health & Social Justice at the University of Saskatchewan. She is the author or editor of several books and articles on the history of psychedelics, including: Psychedelic Psychiatry (2008); Psychedelic Prophets (2018), A Culture’s Catalyst (2016) Wonder Drug (2021), Acid Room (2022); Expanding Mindscapes (2023) and Psychedelics: A Visual Odyssey (2024). Erika was the co-editor of the Canadian Journal of Health History (2015-2023) and is currently the President of the Alcohol and Drugs History Society. She is also a co-editor of the recently published, Women and Psychedelics: Uncovering Invisible Voices (2024).

Mikaela de la Myco comes from a blended ancestry. Her ancestors come from southern italy, the caribbean and mexico and she uplifts their perspectives in the space of entheogens.In her everyday life, Mikaela serves as a mother, an educator, a folk herbalist, a community organizer and entheogen facilitator in occupied Kumeyaay & Luiseno territory, also known as San Diego, CA. She cares for all people with ancestral healing ways and holds special focus in serving small-businesses, cooperatives, non-monogamous people, psychedelic families, femmes and people seeking full-spectrum herbal womb care. She has collaborated as an educator and activist with hundreds of companies and organizations within the sacred earth medicine space and is well known as a maternal caretaker in the community. Her platforms, Mama de la Myco and the mushWOMB generate educational content that weaves the tapestry of medicine woman, psychedelic mother and sacred hoe. In all her creations, Mikaela de la Myco has made the commitment to rematriate entheogens by advocating for ethics and womb to tomb psychedelic literacy. Her most recent movement, Mothers of the Mushroom is an open source research and resources project meant to further permission the world into remembering that psychedelics are for families.

Maria Mangini, PhD, FNP, completed her doctorate in Community Health Nursing at University of California, San Francisco, where her research on drugs and drug policy explored the impact of historic LSD use in the lives of middle-aged adults. She was the director of the MSN/FNP program at Holy Names University in Oakland for 20 years. For 25 years, she was in family practice with Frank Lucido MD, and theirs was one of the first to add medical cannabis to the family practice armamentarium. She is co-founder of the Women’s Visionary Council, which supports the work of women scholars, artists, healers and visionaries through a series of conferences, workshops and grants. Her interests currently center on the study of death and dying.

Belinda Eriacho is of Dine’ (Navajo) and A:shiwi (Pueblo of Zuni) descent. Her maternal clan is One-Who-Walks-Around and she was born for the Zuni Pueblo people. Belinda was born and raised on the Navajo reservation, located in Arizona, United States of America. She is the wisdom carrier, healer, and founder of Kaalogii LLC, focused on cultural and traditional teaching, inner healing, and an international speaker on various topics impacting Native American communities in the United States. Belinda holds degrees in Health Sciences, Technology, and Public Health. In addition, Belinda has participated in the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies, MDMA People of Color, and Eye Desensitization and Reprocessing Therapy Training Programs. Belinda is also a Founder and Board member of the Church of the Eagle and the Condor, a Program Advisor for Naropa University, and a Native American Traditional Advisor for SoundMind. She is the author recent articles that are available on charuna.net: “Considerations for Psychedelic Therapist when working with Native American People and Communities”, “Guidelines for Inclusion of Indigenous People into Psychedelic Science Conferences” and “This is not Native American History, this is US History with Belinda Eriacho”. In addition, a contributing author to the recently published Psychedelic Justice: Toward a Diverse and Equitable Psychedelic Culture (Synergetic Press, 2021).

Fernanda Baraybar is a transpersonal psychologist, marketing specialist, writer, and practicing Shaman. Working with the Qero communities of Peru, she’s helping keep her ancestors’ traditions alive by learning from their ancient practices. Currently, she’s working as a Marketing Freelance Consultant for Synergetic Press, her passion moves her to create for organisations focused on the expansion of consciousness. She is pursuing an MSc in Spirituality, Consciousness, and Transpersonal Psychology at the Alef Trust with the aim of creating further research on parapsychological phenomena.

Blending historical and anthropological approaches with a series of captivating interviews, this collection taps into women’s networks around the world throughout the 20th century. It reveals some of the sophisticated and creative ways women have influenced our understanding of psychedelics and how they will continue to protect these stories as we face our psychedelic future. Our collection intentionally moves beyond an American set of stories, teasing out networks in Latin America. This collection brings together authors from the Chacruna Institute and Chacruna Latinamérica to engage readers in conversations that move across time and place throughout the Americas. It is the first of its kind to balance non-English contributions through translation of stories exploring different cultural contexts outside the United States, where women have contributed to this enduring history.