Celebrated psychotherapist Claudio Naranjo‘s last work as an author makes a final call to humanity to awaken to our collective potential and work to transcend our patriarchal past and present in order to build a new world. This book argues not only for a collective individual awakening, but a concerted effort to transform our institutions so that they are in service to a better world. Naranjo targets our traditional education and global economic systems that increasingly neglect human development and must transform to meet the needs of future social evolution. Ultimately, he says, we need to embark on a collective process of rehumanizing our systems and establishing self-awareness as individuals to create the necessary global consciousness to realize a new path forward; stressing the need for education to teach wisdom over knowledge, and utilizing meditation and contemplative practices to form new ways to educate, and be educated.

Continuing the Shulgin Legacy: Synergetic Press & Transform Press Agree to a Co-Publishing Deal

Synergetic Press is excited to announce that we have very recently signed a co-publishing deal with Transform Press, and are set to publish a new series of Transform Press titles by Alexander and Ann Shulgin, in continuation of the Shulgin legacy. Transform Press books are now distributed through Publishers Group West, effective July 1, 2020

Since 1984, we at Synergetic Press have published in the areas of ecology, ethnobotany, anthropology as well as psychedelic history and research. Transform Press was founded in 1991 by renowned biochemist Alexander “Sasha” Shulgin and his wife and co-author, Ann Shulgin, to publish their groundbreaking classic, PiHKAL: A Chemical Love Story and has specialized in works on psychopharmacology, psychedelic drug research, and other material relating to psychoactive compounds, states of consciousness, and society.

“Over the past three decades, both Synergetic Press and Transform Press have been publishing pivotal books in specialized topics of plant medicine and psychedelic psychotherapy, each cultivating important hubs for scholarship and public discourse through events and symposiums,” said Deborah Parrish Snyder, Publisher, and CEO of Synergetic Press.

“We are honored to work together with Wendy Tucker, Publisher, and CEO of Transform Press, her mother Ann Shulgin, and their team to bring out more of the pioneering work by the Shulgins’.”

“Transform Press has many projects in the pipeline. We’re very happy to be able to work with the team at Synergetic Press to broaden our reach to the public and to contribute to the ever-expanding field of psychedelic research and its history,” said Wendy Tucker.

“This is an exciting time, as information about psychedelic drugs is not being demonized as it was before,” Tucker added. “Instead it is being seen more through a lens of curiosity as to the potentials for healing and growth.”

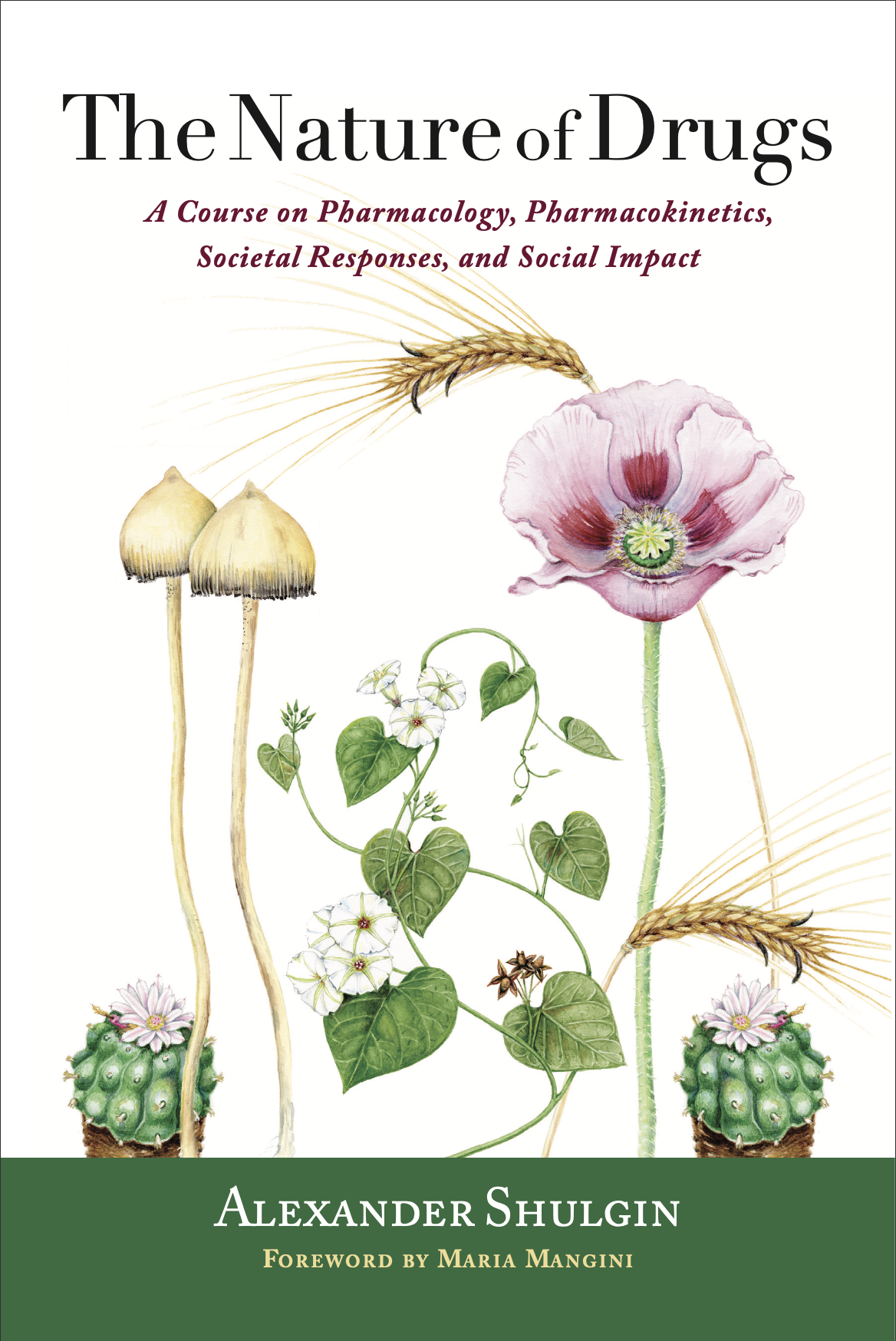

Our First Co-published Book: The Nature of Drugs

The first co-published title, to be released in Spring 2021, will be The Nature of Drugs: A Course on Pharmacology, Pharmacokinetics, Societal Responses, and Social Impact based on a lecture series that Sasha Shulgin taught (by the same name) at San Francisco State University (SFSU).

The full text was transcribed from the original lecture tapes recorded at SFSU in 1987 and will be published in two consecutive volumes. Volume I covers the first third of the course and presents Sasha’s views on the origin of drugs, the history of U.S. drug law enforcement, human anatomy, the nervous system, the range of drug administrations, varieties of drug actions, memory and states of consciousness, and research methods. The discussions in The Nature of Drugs lay the groundwork for Sasha’s philosophy on psychopharmacology and society, what defines a drug, the nature of a person’s relationship with a given compound, and for extensive examinations of dozens of compounds in Volumes II. The book chronicles the story of humanity’s relationship with psychoactive substances from the perspective of a master psychopharmacologist and will enthrall anyone intrigued by this subject.

“For those of us who were not fortunate enough to attend Sasha’s classes, this book is a fantastic second chance to learn from a brilliant, principled, courageous, idealistic psychedelic chemist whose creations were molecules for psychotherapy, spirituality, and celebration, to help humanity wake up and save ourselves.” — Rick Doblin, Founder and Executive Director of the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS)

Beyond this, there are plans for three additional books carrying on the Shulgin legacy, including a second volume of The Nature of Drugs, a book of letters from the Shulgin archive, and a third volume of work joining the PiHKAL-TiHKAL series.

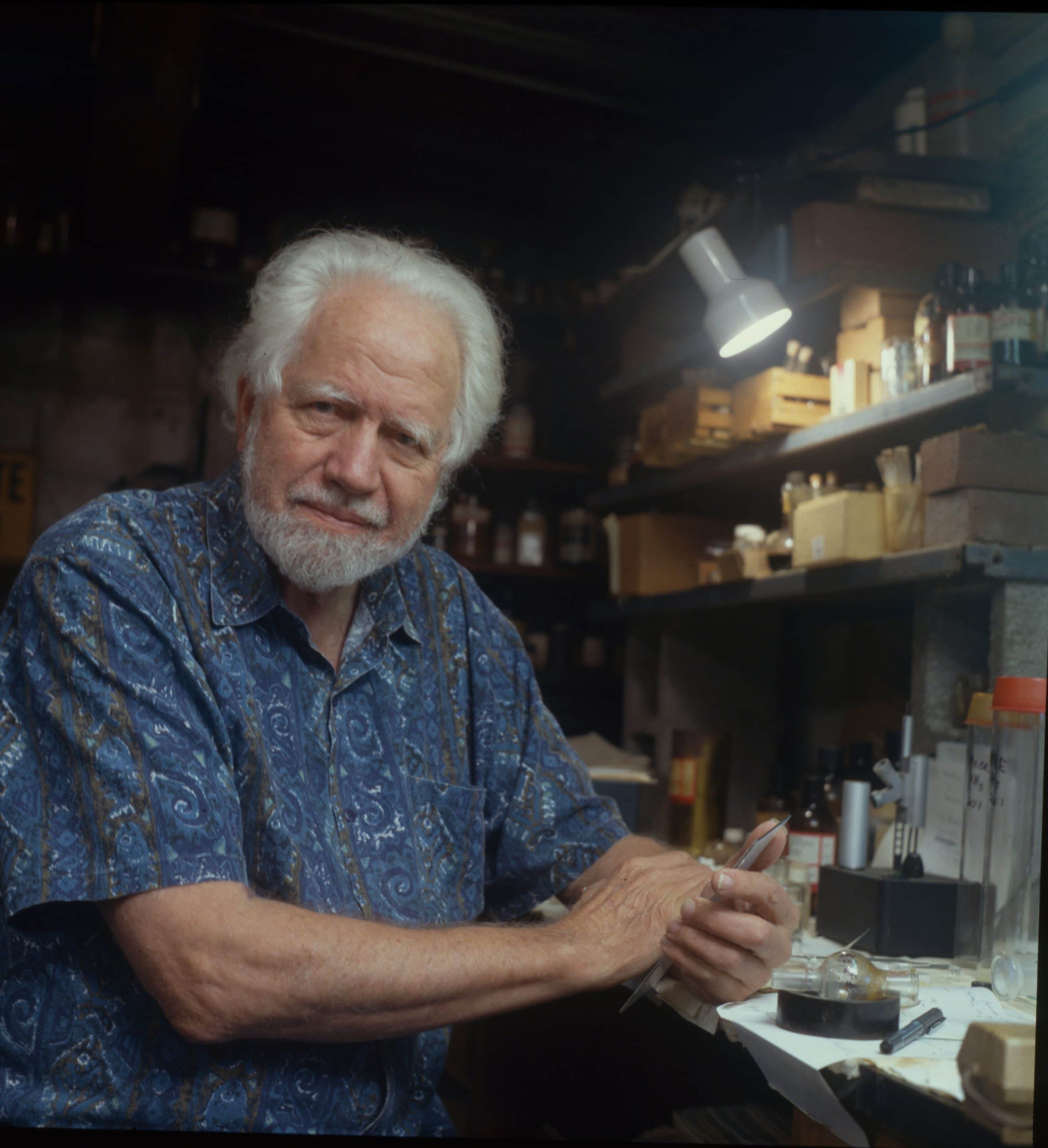

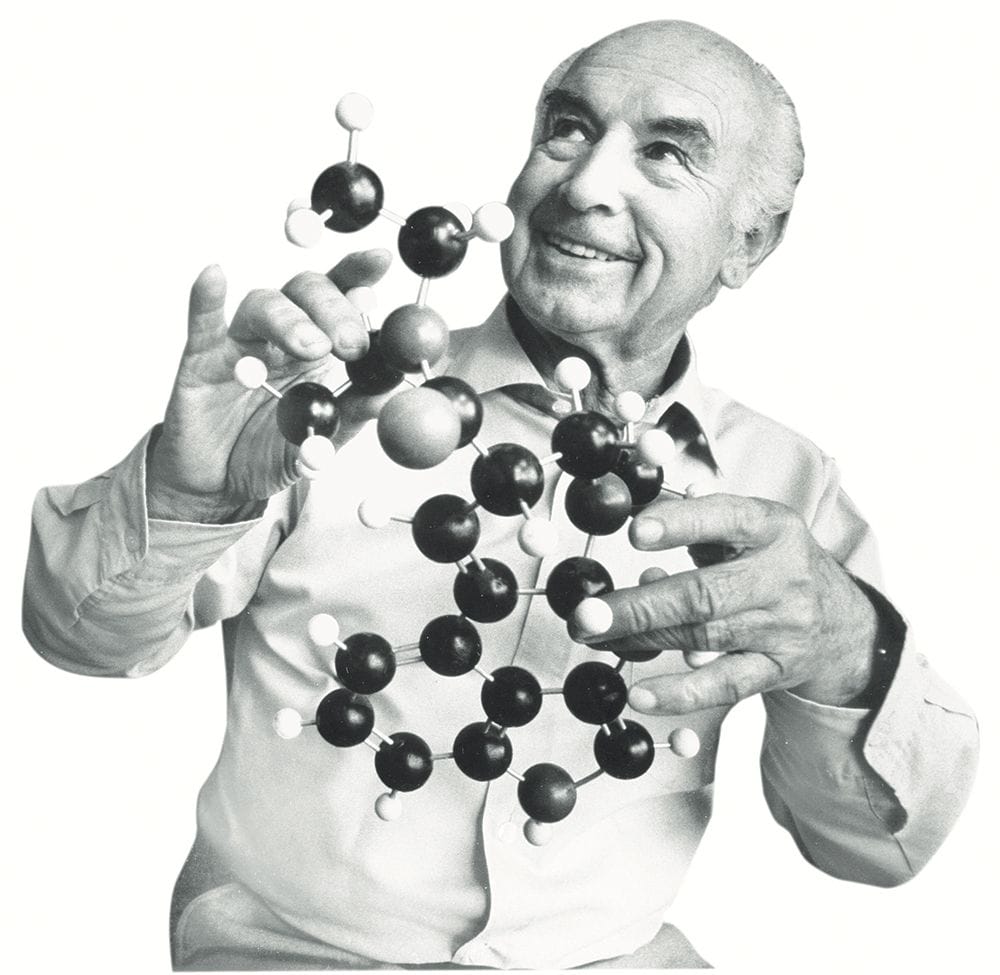

Alexander Shulgin, The Most Prolific Psychedelic Chemist in History

Alexander Shulgin, The Most Prolific Psychedelic Chemist in History

The late Alexander “Sasha” Shulgin was undoubtedly one of the most pioneering chemists of this century. Completing his Ph.D. in biochemistry at the University of California, Berkeley in 1955, Shulgin went on to get a job at the Dow Chemical Company, where he invented a highly lucrative, world’s first biodegradable pesticide by the name of Zectran (mexacarbate).

Whilst working at Dow in 1960, Shulgin had his first mind-altering experience. He ingested mescaline, a psychedelic compound that is naturally found in the peyote cactus, finding it so astounding that he dedicated the rest of his career to exploring psychedelic chemistry.

“I first explored mescaline in the late ’50s,” Shulgin said in a 1995 interview. “Three-hundred-fifty to 400 milligrams. I learned there was a great deal inside me.”

Dow, pleased with his work, and the high profits generated by Zectran, gave him the freedom to pursue his own research program, and thus his experimentation with synthesizing psychoactive substances began.

Shulgin left Dow in 1966, supporting himself thereafter by becoming a scientific consultant as well as a lecturer and teacher. Setting up a home-based laboratory on his ranch in Lafayette, California, he synthesized more than two hundred novel psychoactive compounds. Perhaps ironically, the US Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) gave him permission to do so, even calling on Shulgin to serve as an expert witness in drug trials.

A bold explorer of the frontiers of neurochemistry, Shulgin tested the majority of the substances he synthesized on himself, his wife and co-researcher Ann, and a small circle of trusted friends. He and his friends kept diligent notes on their experiential research forays.

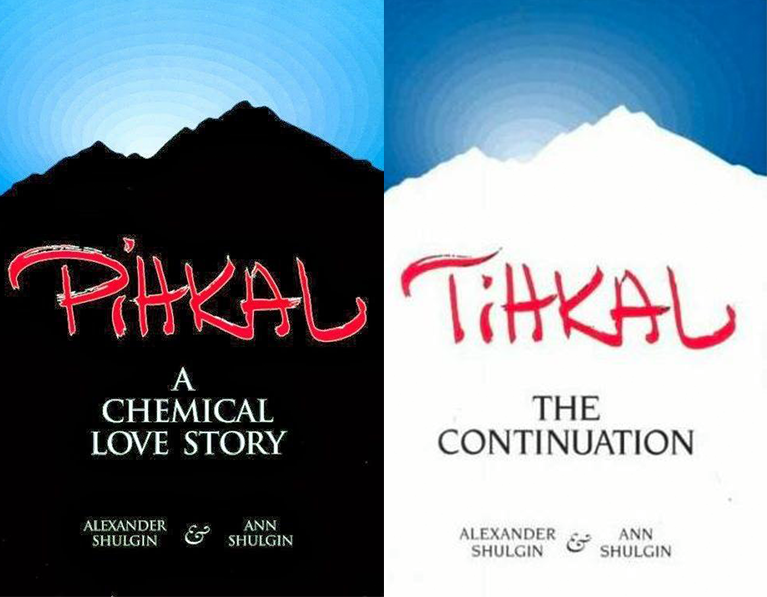

Wanting to ensure that his life’s work researching psychoactive compounds did not disappear with him, he and his wife Ann, co-authored the psychonautic tome, PiHKAL: A Chemical Love Story in 1991. ‘PiHKAL’ is an abbreviation for “Phenethylamines I have known and loved.” Phenethylamines are a class of natural and synthetic compounds, some with powerful psychoactive properties, including the naturally occurring mescaline, and the synthetic methylenedioxymethamphetamine, otherwise known as MDMA.

PiHKAL, jointly written by Sasha and Ann Shulgin, is the fictionalized autobiography that blends the personal history of their falling in love with carefully detailed descriptions for how to synthesize 179 psychoactive compounds.

In 1996, the Shulgin’s published TiHKAL, a sequel to PiHKAL, standing for “tryptamines I have known and loved.” Tryptamines include well-known psychedelic substances like psilocybin, DMT, and the neurotransmitter serotonin. Similar to PiHKAL, TiHKAL is divided into two parts and is a blend of personal history and chemical recipes.

In 1996, the Shulgin’s published TiHKAL, a sequel to PiHKAL, standing for “tryptamines I have known and loved.” Tryptamines include well-known psychedelic substances like psilocybin, DMT, and the neurotransmitter serotonin. Similar to PiHKAL, TiHKAL is divided into two parts and is a blend of personal history and chemical recipes.

Shulgin is most often remembered for his re-discovery and synthesis of a chemical called 3,4-methylenedioxy-N-methylamphetamine, otherwise known as MDMA. MDMA was originally synthesized by German chemist Anton Köllisch in 1912, however, when Shulgin resynthesized the chemical, he discovered that it had potent psychoactive properties.

Discovering its effects, Shulgin suggested that MDMA would be a powerful aid in therapy, and by the late 1970s, some of his colleagues were evaluating the drug’s use in therapeutic settings. However, MDMA soon escaped the therapeutic setting, rising to popularity amongst young partygoers where MDMA’s euphoric effects were soon rebranded by dealers as “ecstasy” and MDMA was reclassified as a Schedule I drug in 1985.

Shulgin lamented the reckless recreational use and ensuing prohibition of psychedelics in that it hindered the possibility of their legitimate use in psychotherapy.

“Use them [psychedelics] with care, and use them with respect as to the transformations they can achieve, and you have an extraordinary research tool. Go banging about with a psychedelic drug for a Saturday night turn-on, and you can get into a really bad place, psychologically. Know what you’re using, decide just why you’re using it, and you can have a rich experience. They’re not addictive, and they’re certainly not escapist, either, but they’re exceptionally valuable tools for understanding the human mind, and how it works.” ― Alexander Shulgin, PiHKAL: A Chemical Love Story

These books, combined with Shulgin’s association with MDMA were responsible for his rapid rise to popularity, and his becoming a celebrated chemist world over.

Exploring the Shulgin’s Chemical Legacy

Exploring the Shulgin’s Chemical Legacy

A new Netflix documentary series The Business of Drugs set out to investigate the economics of six illicit substances, including synthetic drugs like MDMA. The second episode, entitled “Synthetics” is devoted to exploring the chemical legacy that Alexander Shulgin left in his wake.

“The century of the synthetic drug begins but doesn’t end in the shadow of the late Alexander Shulgin. In the 1960s, Alexander “Sasha” Shulgin, a renegade chemist reimagined the study of drugs, and by extension human consciousness. He is recognized as the “spiritual father of psychedelics”, creating over two hundred substances from scratch, but he also, however, inadvertently set off the billion-dollar race to control the synthetics market.”

The episode navigates the dangers of synthetics, but continually circles back to the fact Shulgin saw breakthrough therapeutic potential in MDMA, the synthetic drug that brought him his fame. Shulgin never suspected that MDMA and other substances that he synthesized would become popular amongst young partygoers. Rather, he saw them as revolutionary psychotherapeutic tools that the “War on Drugs” wrongly forced underground.

Image: Ann Shulgin with daughter, Wendy Tucker, Publisher at Transform Press (Photo by Audrey Tucker, 2020)

“Spaceship Earth” the Film

“Spaceship Earth” the Film

By

By