What is Psychedelic Justice?

As psychedelics integrate into dominant culture, the question of what forces will shape the direction of the psychedelic renaissance is front and center. Those of us who believe that psychedelics can help transform society by allowing us to operate out of the sense of interconnectedness they inspire are being challenged to define and embody, the values that drive this growing movement.

In the past few years, the term “psychedelic justice” has surfaced in a multitude of psychedelic spaces as a lens for addressing deep-rooted injustices within the community, and cultivating a movement that serves the needs of everyone – particularly those who have been historically marginalized and oppressed.

In this spirit, the upcoming anthology Psychedelic Justice: Toward a Diverse and Equitable Psychedelic Culture, edited by Bia Labate and Clancy Cavnar, compiles essays written for the Chacruna Institute that examine a myriad of issues facing the psychedelic community through the lens of psychedelic justice, and offer solutions for mending them. Among the wide spectrum of topics explored in this anthology are diversity and inclusion, reciprocity, abuses of power within psychedelic spaces, policy, sustainability, capitalism, and colonialism.

Below are some instances of the term’s usage, and is by no means an exhaustive list of when and how the notion of psychedelic justice resonates.

Psychedelics and Drug Policy

Back in 2017, Jag Davies, at the time the communications director for the Drug Policy Alliance, used the lens of psychedelic justice to discuss why decriminalization is a necessary step towards repairing the harms of the drug war, which has incarcerated thousands of people yearly for using psychedelic substances, and disproportionately impacts “young, nonwhite and socioeconomically marginalized” people.

As research into the therapeutic benefits of these medicines becomes legitimized, heading towards legal medicines for those who have access, the notion of psychedelic justice begs the question that Davies posed:

“What would it mean if we end up in a world where psychedelics are legally accessible for a privileged few, while communities who have historically suffered the worst harms of prohibition remain criminalized? For social change to be truly transformational, mustn’t it lift up those who are the least privileged among us?”

Since 2019, movements to reform drug policy have sprung up across the country, and psychedelics have been decriminalized in Oakland, Washington, DC, Santa Cruz, Somerville, Ann Arbor, Cambridge, and the state of Oregon, with currently active decriminalization bills and ballot initiatives in motion across the country. Many of these movements have broadened their scope to include all drugs, not just psychedelics, a move that aims to dismantle psychedelic exceptionalism and the hierarchy of drug users, and seeks to protect all forms of altered consciousness.

Capitalism and Psychedelics

The question of what values are shaping this renaissance is of particular concern regarding the booming psychedelic industry, which is projected to reach $10.75 billion by 2027. What does it look like when psychedelics enter a competitive market whose strictly profit-driven logic dictates that ruthless competition trumps the spirit of open-sharing and cooperation?

Historically, psychedelics have been researched and developed by those in the underground – the “outlaws,” as Erik Davis puts it in his essay “Capitalism on Psychedelics.” The “writers, healers, freaks, and wizards” who made up the underground and gathered at psychedelic conferences oriented themselves around the values of sharing information, mutual respect, and operating out of service for the community of substance users, explains Davis.

Today, the emergence of psychedelic companies that operate in the traditionally capitalist spirit of snuffing out competitors and monopolizing a profitable product is enormously troubling to many in the psychedelic community who align with the values described by Davis, including Johns Hopkins researcher Bob Jesse, who spoke about the merging of psychedelics and capitalism at the 2018 “Cultural and Political Perspectives on Psychedelic Science.”

“When given under propitious circumstances—with a measure of grace,” Jesse said of psychedelics, “some would say they fairly reliably lead to experiences which are frequently beyond words and frequently change lives. When that phenomenon occurs, it is my wish that that happens in the best possible, cleanest space, being held by people who are very clear about their motives.”

Psychedelics and Reciprocity

While some companies profit off psychedelics, they lack, as Celina De Leon writes on Chacruna, “any clear channel for reciprocity toward Indigenous and traditional communities where these practices originate.” The ritual knowledge surrounding these sacraments is foundational to Indigenous communities in the Americas that continue to this day and inform the Western medical perspective of psychedelics.

“The very protocols that exist today draw upon many of the perspectives and insights that leaders in the field experienced while engaging with these substances, either directly with Indigenous communities or in so-called ‘underground’ settings,” writes De Leon. Directly supporting projects that are “indigenous-led or facilitated by individuals that have long-standing relationships in indigenous and traditional plant medicine communities is a great step,” suggests Leon, who points to these initiatives.

Listening to Indigenous voices is crucial as we continue to benefit from the plant medicines that play an integral role in their traditions. This has been made abundantly clear in the realm of drug policy, where the justice of decriminalization is complicated by the issue of peyote scarcity, which affects the Indigenous communities for whom the cactus has served as an ritual sacrament for centuries.

The National Council of Native American Churches (NCANC) and the Board of the Indigenous Peyote Conservation Initiative (IPCI) definitively voiced their stance on the matter in a 2020 statement, saying that due the peyote shortage, which is impacted by the peyote black market and unsustainable harvesting practices, peyote should not be included in decriminalization efforts, which would likely lead to further destructive behavior.

As they write in their statement, “For non-native persons who want to avail themselves of relationships with entheogenic healing medicines that don’t harm the very fragile peyote population in south Texas or disrespect the spiritual and cultural norms of our Indigenous peoples, they should look for alternative medicines.”

Prejudice and Abuse within Psychedelic Spaces

Although the psychedelic experience may contribute to increased empathy towards others, psychedelic communities are not immune to prejudice and abuse. Now, as society faces a reckoning for the oppression and abuse that marginalized groups have faced for decades, the psychedelic community, too, is being tasked to co its own shadow side, and address these inequities.

Up until recently, the public face of Western psychedelic discourse has been dominated by white men. While the likes of Terence McKenna, Ram Dass, Timothy Leary, Aldous Huxley, and Alan Watts are formidable voices, a movement whose representation reflects the same biases of Western society at large, can only be stunted by such a limitation in the long run, as it only reinforces the same age-old structural inequities. Whether conscious or unconscious, racism, sexism, and other forms of discrimination are still prevalent and are structurally embedded within these communities.

Psychedelic science, for example, is still plagued by a lack of diversity and representation, both among researchers and participants. “People of color and women are uncommon in leadership positions in the psychedelic research community,” write clinical psychologist Monnica T. Williams and Chacruna founder Bia Labate in the Journal of Psychedelic Studies, “and few people of color are included as research participants in psychedelic studies.”

And as psychologist and psychedelic researcher Alex Belser points out, psychedelic research is still informed by heternormative stereotypes about gender roles, with research from past 15 years treating cisgender, straight people as the default.

“Although it is exciting to witness the culmination of decades of drug policy advocacy and clinical research, the psychedelic science movement struggles with many of the same social issues that plague healthcare in general,” write Williams and Labate.

Psychedelic spaces are not immaculate respites from abusive behavior, either. Sexual abuse at the hands of shamans in traditional ceremonial contexts is unfortunately not uncommon, with a number of individuals sharing their accounts of being sexually exploited by someone they entrusted with their healing journey. Even in clinical psychedelic therapy, sexual abuse is not unheard of.

It may be difficult to reconcile the bathed-in-pure-love sensation of a psychedelic experience with abusive, toxic behavior at the hands of those facilitating it, especially when they are perceived as being part of a more spiritually evolved tradition.

“Increasing awareness of sexual abuse and exploitation by ayahuasqueros and other healers has been disconcerting for the psychedelic community, where ‘shamans’ are often idealized and romanticized,” writes somatic sex educator Britta Love on Chacruna. “The medicalization of psychedelics will no doubt mean we soon find our legitimized Western psychedelic gatekeepers just as imperfect as their indigenous and underground counterparts.”

***

“If the psychedelic renaissance is to grow and be able to bring healing and benefits for humanity, it has to include everybody,” shared Labate at the 2019 Bioneers Conference.

Her words reflect a core essence of psychedelic justice: the commitment to transmuting the blissful oneness felt by any one individual during their psychedelic journey into an enduring ethical compass with which they navigate and serve their communities, and the values they are unwilling to compromise as the psychedelic movement grows.

***

More about Psychedelic Justice

Radical, cultural transformation is the guiding force behind this socially visionary anthology. Its unifying value is social justice. It guides us in cultivating a psychedelic renaissance that represents everyone, honors voices that have been suppressed for too long, and envisions a more beautiful tomorrow through a psychedelic lens.

Radical, cultural transformation is the guiding force behind this socially visionary anthology. Its unifying value is social justice. It guides us in cultivating a psychedelic renaissance that represents everyone, honors voices that have been suppressed for too long, and envisions a more beautiful tomorrow through a psychedelic lens.

Psychedelic Justice highlights Chacruna’s ongoing work promoting diversity and inclusion by prominently featuring voices that have long been marginalized in Western psychedelic culture: women, queer people, people of color, and indigenous people. The essays examine both historical and current issues within psychedelics that many may not know about, and orient around policy, reciprocity, diversity and inclusion, sex and power, colonialism, and indigenous concerns. We believe the book can be another tool to help Chacruna and its allies continue to push for justice and inclusion in the greater psychedelic culture.

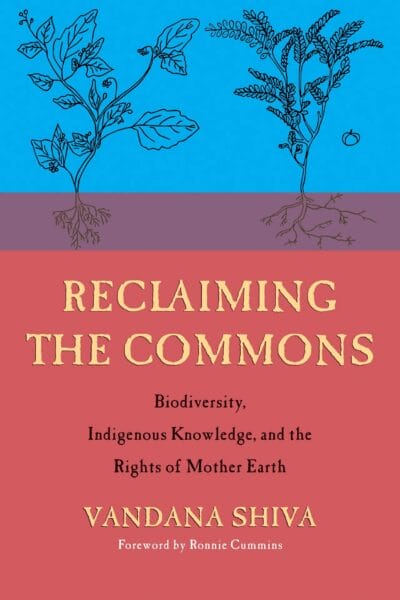

Reclaiming the Commons

Reclaiming the Commons